By John Schamel

Nocturnal Travels

According to the technical forecasters of today, aircraft in the next century will finally lose their bonds to Earth. The use of the Global Positioning System (GPS) will allow freer flight by unleashing aircraft from their ground based navigation systems. By placing new technology into aircraft, navigation would be provided by a network of 24 satellites instead of the current ground based system of slightly over 2,000 navigational aids.

Today’s aircraft still find their way by using airways and their ground-based navigational systems based on the development of the VOR, DME, and ILS since World War Two. Today’s airways, though, trace their roots to a time before radio.

After World War One, the U.S. Post Office began operating a series of air mail routes along the East Coast. On August 20, 1920, the Transcontinental Air Mail Route was opened. Extending from New York to San Francisco, it was the first airway to cross the nation. Airways in those days were merely concepts – air navigation charts didn’t exist. Pilots used railroad or early road maps since flying was a fair weather daytime activity. Mail planes of the day normally came equipped with a compass, a turn-and-bank indicator, and an altimeter. Pilots were often skeptical of their instruments and would only fly along a well-known route.

And there was the problem. Mail could only fly in the daylight. Many skeptics looked at Air Mail as an expensive frill, since it offered no clear-cut savings in time. Mail could cross the nation by rail in three days. The short daylight hops aircraft could give to the mail weren’t cost effective.

Paul Henderson, who became the Second Assistant Postmaster General in 1922, agreed that Air Mail was an expensive fad. He recognized, like others before him, that Air Mail would become profitable only when it became a round-the-clock operation.

Fortunately, Paul had proof that it could be done. In February 1921, a grand experiment had been conducted. Two flights would fly the Transcontinental, one in each direction and the flights would continue into the night. Despite a raging blizzard across the Great Plains and the Midwest, one flight was able to make it with its load of mail from San Francisco to New York. The determination of one pilot, Jack Knight, who flew three segments of the route, made it succeed. Jack was able to find his way across the snow swept plains by following the bonfires lit by supportive citizens and postal employees.

Using six aircraft and six pilots, the air mail relay took slightly more than 24 hours to cover the distance from San Francisco to New York. Proof of substantial timesaving was made.

Henderson saw what was needed. “An airway exists on the ground, not in the air”. A 1923 experiment conducted by the Army Air Corps in Ohio showed that pilots could navigate at night using rotating light beacons. With this example, Henderson was able to press his requests for the development of a similar system for the Air Mail routes. Congress, in 1923, approved funding for the lighting of the Transcontinental Air Mail Route. Work started immediately on the Cheyenne to Chicago segment. Being in the middle of the nation, flights starting at daybreak on the coasts would be able to fly to either end of the lighted segment before dusk.

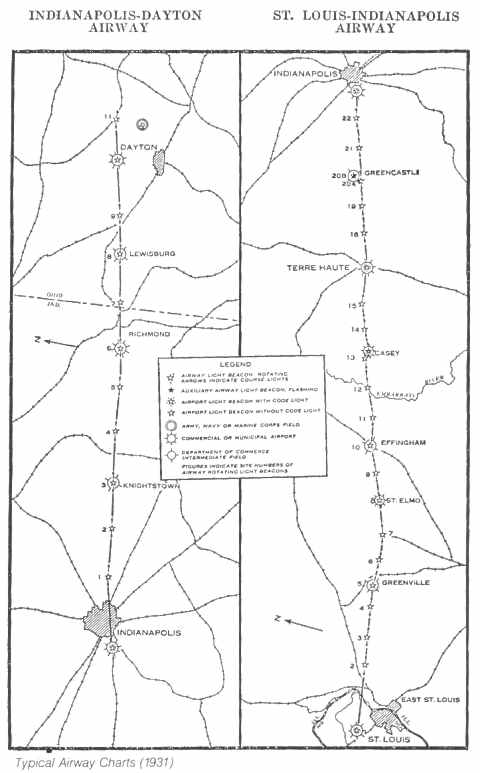

St. Louis, Missouri to Dayton, Ohio via Indianapolis

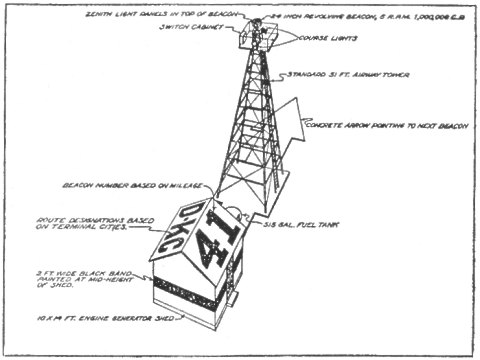

| What resulted was the first ground based civilian navigation system in the world. Beacons were positioned every ten miles along the airway. At the top of a 51-foot steel tower was a 1 million candlepower-rotating beacon. Pilots could see the clear flash of light from a distance of 40 miles. Also at the top of the tower were two color-coded 100,000 candlepower course lights. These pointed up and down the airway. They were colored green, signifying an adjacent airfield, and red, signifying no airfield. The course lights also flashed a Morse code letter. The letter corresponded to the number of the beacon within a 100-mile segment of the airway. To determine their position, a pilot simply had to remember this phrase – “When Undertaking Very Hard Routes, Keep Direction By Good Methods” – and know which 100-mile segment they were on. |

The beacons were also built to aid daytime navigation. Each tower was built on an arrow shaped concrete slab that was painted yellow. The arrow pointed to the next higher numbered beacon. An equipment/generator shed next to the tower had the beacon number and other information painted on the roof.

Regular scheduled night service on the Transcontinental Air Mail Route started on July 1, 1924. Now operating around the clock, Air Mail was able to cross the nation in 34 hours westbound and 29 hours eastbound. By the fall of 1924, the lighted segment extended from Rock Springs, WY to Cleveland, OH. By the summer of 1925, it extended all the way to New York.

An English aviation journalist, visiting the U.S. in 1924, wrote, “The U.S. Post Office runs what is far and away the most efficiently organized and efficiently managed Civil Aviation undertaking in the World.”

On July 1, 1927, the U.S. Post Office ended its Air Mail operation. The Transcontinental Air Mail Route, and other air mail routes, were turned over to the fledgling Airways Division in the Commerce Department’s Bureau of Lighthouses. The Airways Division continued with the development of lighted airways. An improved version of the beacon was fielded in 1931.

On January 29, 1929, the rotating beacon at Miriam, NV was turned on, lighting the last beacon in the Transcontinental Air Mail Route.

By 1933, the Federal Airway System operated by the Airways Division comprised 18,000 miles of lighted airways containing 1,550 rotating beacons and 236 intermediate landing fields. Air Mail pilots routinely navigated the skies during the night, following the “signposts” of the rotating beacons.

About the author …

John joined the FAA in 1984 and has been an Academy instructor since 1991. He taught primarily in the Flight Service Initial Qualification and En Route Flight Advisory Service programs. He has also taught in the International and the Air Traffic Basics training programs at the FAA Academy.

History has been an interest and hobby since childhood, when he lived near many Revolutionary War and Great Rebellion battlefields and sites. His hobby became a part time job for a while as a wing historian for the U.S. Air Force Reserve.

John’s first major historical project for the FAA was to help mark the 75th Anniversary of Flight Service in 1995.